Needlework

The Royal Dublin Society (RDS), founded in 1731, encouraged crafts and offered valuable prizes for excellence. Several schools trained women to produce lace for the lively social life of the ascendancy class and the court at Dublin.

Throughout the ninenteenth century, there was a demand for lace to adorn the hair, neck, cuffs and underwear of the well-off. Vast amounts were produced for weddings, christenings and mourning. Lace also embellished table linen, curtains and bed linen. Clergy and hierarchy created a demand for exquisite lace to decorate the edges of altar cloths and white vestments.

When the domestic linen industry collapsed, alternative opportunities were sought for women in the home. Lace-making, crochet, embroidery and 'flowering' (embroidering sprigs of flowers on muslin) enterprises were started up in many towns by women who were wealthy, educated or well-travelled, and often by nuns.

Mrs Grey Porter, wife of a rector, brought back new ideas for lace-making from her honeymoon in Italy to Carrickmacross in 1816 and the town acquired a reputation for the craft. Tristram Kennedy in 1846 organised schools for training and design and when he became an MP in London, obtained an order for Carrickmacross lace from Queen Victoria. After a decline in his enterprise, the St. Louis Convent founded in Carrickmacross in 1860 became the custodian of the local lace tradition and 130 women were employed in the trade there in 1887.

|

Lace workers from Nottingham were introduced to Limerick by Charles Walker in 1829 and a considerable industry developed over the years. By the 1850s, over 1,500 workers were employed, some in their own homes. After a decline, the Limerick tradition came to rest in the Good Shepherd convent there.

Many convents organised groups of lace makers. The Presentation Convent at Youghal opened a school after the Famine and the Ursulines in Cork introduced Irish crochet. Clones, Kells, Kilrush, Kinsale, Kenmare and Mountmellick were among several other lace-making and needlework centres.

|

Lace dress

Sheelin antique Irish lace museum |

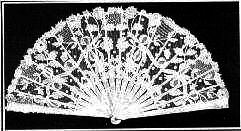

Lace fan

Sheelin antique Irish lace museum

Needlework crafts were, at various times, subject to fashion, to poor design and workmanship, to exploitation of women workers and to the rise of cheap machine-made lace and embroidery. Crafts were promoted after the famine for the employment for women. At the end of the nineteenth century, the Congested Districts Board encouraged them and Ishbel, Lady Aberdeen, wife of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland organised and promoted Irish crafts enthusiastically. A large woman in later life, she got the nickname 'Blousy Bella' from wearing many examples of Irish textile crafts at one time. She visited lace-making enterprises, opened a Lace Depôt in Dublin, gave a 'Lace Ball' in Dublin Castle and organised a lace exhibition at the Chicago World's Fair in 1893.

Agnes Morrogh Bernard

Foxford Museum |

Agnes Morrogh-Bernard (Mother Arsenius), a Sister of Charity was determined to help the people of Foxford, Co. Mayo to help themselves. She saw the possibility of using the fast-flowing River Moy to power a woollen mill there and was referred to John Charles Smith of Caledon Mills, Co. Tyrone for advice. |

Although his reply to her letter had commenced with the words: 'Madam, are you aware that you have written to a Protestant and a Freemason?' she remained undaunted by their religious differences. She had no difficulty in accepting diversity and always looked for the best in everyone.

Foxford IRD, Agnes Morrogh-Bernard 1842-1932, Foxford, n.d. |

John Charles Smith was very helpful and she opened the Providence Woollen Mills at Foxford in 1891. The Congested Districts Board recognised her leadership, managerial and marketing skills and they supported her enterprises with loans and grants. Further projects included dairying, poultry and horticultural training, Christmas concerts, sports, a brass and reed band, housing and schools.

Embroidery in many styles was produced for the market, to decorate the home or merely to 'put down time.' Evelyn Gleeson with Elizabeth and Lily Yeats set up the Dun Emer Guild in Dundrum, Co. Dublin and trained women to produce work to a high standard of design in the crafts of embroidery, tapestry and printing.

Bedspreads were often displayed proudly through the open bedroom doors of traditional thatched houses. Patchwork has been popular since at least the eighteenth century, and excellent bedspreads in quilting, crochet and knitting were produced, as well as tablecloths and other such items. Proverbs, verses and other quotations were worked into samplers and provided good advice for girls learning to do fancy needlework.

Knitting of socks, jumpers and baby wear was traditionally done by women and basic knitting was taught to girls in primary schools. Donegal and Aran hand-knit garments are famous the world over. Stitches used in ganseys, caps and stockings have names such as 'ladder of life', 'marriage lines' and 'Irish moss' and they are said to have symbolic meanings.

Many examples of needlework patiently completed over months or years have been preserved and cherished but even when produced to a high standard of workmanship, less value was placed on them generally than on work done to a corresponding standard in drawing or painting, for instance, or in wood or metal.

Irish women fashion designers achieved national and international success in the twentieth century, including Sybil Connolly, Irene Gilbert, Neilí Mulcahy, Pat Crowley, Mary O'Donnell, Mariad Whisker and Louise Kennedy.

Questions

- List four enterprises set up as alternatives to the domestic linen industry.

- Outline the contributions of any four of the following to economic progress: Mrs Grey Porter; Charles Walker; Lady Aberdeen; Agnes Morrogh-Bernard; Evelyn Gleeson; Elizabeth Yeats; Lily Yeats; a convent of your choice.

Activities

- Research and write an essay on Irish lace.

- Research the production of lace or any other needlework craft in your area. Enquire in convents, drapery stores, homes of known patrons, practitioners, etc.

- Research one or more needlework crafts in some of the many books on the subject and do a project on the topic.

- Interview a person skilled in needlework. What materials, skills and amount of time are involved? Perhaps make recordings, drawings and take photographs.

- Organise an exhibition of needlework crafts: lace, embroidery, knitting, crochet, patchwork, quilting, samplers, etc.

- Organise a 'Lace Parade', a 'Lace Party' or a 'Craft Party'. Be imaginative in how you wear or use veils, table cloths, neck wear, baby wear, etc. but do be careful not to damage the material.

- Organise a visit to a museum which exhibits needlework crafts.