National Maternity Hospital

Holles St., Dublin. Founded 1884

Despite advances in medicine and hygiene since the nineteenth century, the rates of maternal mortality (the rate at which mothers died in childbirth) and of infant mortality in Ireland gave cause for concern for many years. Local authorities, such as county councils were permitted, but not obliged, to provide services for mothers and children but not all of them did so.

|

The maternal mortality rate, at about 5 deaths per 1,000 births, was only slightly better than during the war years and the infant mortality rate in 1928, while an improvement on previous years, remained high at 68 deaths per 1,000 births. The Department was aware of fashionable thinking about pregnancy, particularly the importance of ante-natal care for all expectant mothers and a wholesome diet. But words of encouragement to local authorities to act on their responsibility for maternal welfare fell on deaf ears. In 1930, ante-natal clinics were available only in the four county boroughs. The Department wrung its hands and lamented that 'the problem of ensuring safety in child birth remains unsolved' but refrained from taking the positive action for which the situation called. Only Dublin County Borough could point to considerable progress. |

That greater efforts could have been made was evident in 1933, when the maternal mortality rate for the whole country was 4.44 per 1,000 births but was only .86 per 1,000 births for Dublin.

| The reason was that Dublin had three maternity hospitals and the only extensive maternity and child welfare scheme in the country. Ruth Barrington, Health, Medicine and Politics in Ireland 1900-1970, Dublin, 1987, p.132. |

But infant mortality rates nationwide showed no improvement for many years.

National Maternity Hospital

Holles St., Dublin. Founded 1884

| The death rate among infants would rise to 79 per 1,000 births in 1944 before anyone 'kicked up a row about it.' Ruth Barrington, Health, Medicine and Politics in Ireland 1900-1970, Dublin, 1987, p.131. |

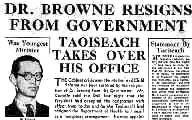

There was pressure for reform in Ireland, especially after the government in England introduced a new National Health Service after the war. The Fianna Fáil government proposed a scheme of free health services for mothers and children in 1945 but lost power after the general election in 1948. A raging debate developed over provisions for mothers and children, especially after Noel Browne became Minister for Health in the new Coalition Government and tried to introduce the Mother and Child Health Scheme.

|

|

|

|

| There have been substantial improvements in maternal and infant mortality rates in recent decades. Infant mortality has declined from 30.5 per 1,000 live births in 1961 to 8.9 in 1985 and 6.6 in 1992. Maternal mortality has declined from 0.25 per 1,000 births in 1971 to about 0.06 in 1985 and 0.04 in 1992. National Report of Ireland to the UN Fourth World Conference on Women, 1994, p.75. |

Many European countries, anxious to increase their populations in the early twentieth century, banned contraception and in Ireland, the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act 1935 prohibited the sale, advertisement and importation of contraceptives.

Several governments tried to attract women back to the home by rewards for child-bearing and discouraged family planning. Pope Pius XI disapproved of birth control and of married women working outside the home. France banned birth control in 1920 and offered medals to mothers of large families: bronze for five children, silver for eight and vermeil for ten or more. Mothers of nine children or seven sons, whichever occurred first, received a special award in Nazi Germany. In Italy, Mussolini offered to meet personally with mothers of fourteen or more children while in the Soviet Union:

| Mothers of ten or more children received the title of Heroine Mother. Bonnie S. Anderson & JP Zinsser, A history of their own: women in Europe from prehistory to the present Vol. II, Penguin Books, p. 210. |

Women who gave birth outside marriage were subject to much stigma in Ireland and Mother and Baby Homes were available to encourage them to hide their pregnancies and give birth in secret while most of their children were reared in orphanages, adopted abroad or fostered. Legal adoption was introduced in Ireland in 1952.